Aramaic Words and Names in the New Testament

In the first two studies we took a brief look at Aramaic and the role it is said to have played in the events and composition of the New Testament. Coupled with this we took a look at several passages in the New Testament where Aramaic is alleged to appear. We found that Mark presents Yeshua speaking Aramaic several times, but in the only instance where one of these events is recorded outside of Mark the evidence shows that Yeshua actually spoke Hebrew on that occasion. Mark’s peculiar use of Aramaic seems to have been a stylistic usage rather than an actual verbatim historical record. To wrap up some issues raised by these previous articles a brief word needs to be said about a variety of terms that appear transliterated in Greek in the New Testament, with an apparent Aramaic morphology (spelling). Below are some examples, with an occasional comment. I will discuss these briefly and then move on to take a more in-depth look at the History of the Hebrew language and the later Hebrew sources which address the linguistic landscape of the late Second Temple Period.

– – Raca (Matt. 5:22) – Aramaic morphology, also exists in Mishnaic Hebrew

– – Rabboni (John 20:16) – May be either Aramaic or Hebrew

– – Maranatha (1 Cor. 16:22) – Aramaic (מרן אתא – come Lord)

– – Pool of Siloam (John 9:7) Explained as meaning “sent” (Hebrew: שלוח)

– – Akeldama (חקל דמא – field of blood – Acts 1:19)

– – Gabbatha (John 19:13) called Εβραιστι, Hebrew

– – “Bar”

– – Barabas (Bar Abbas)

– – Barsabbas (Bar Sabas – Acts 1:23; 15:22)

– – Barnabas (Bar Nabas)

– – Bartemeus (Bar Timaeus – Mark 10:46))

– – Bartholomew (Bar Ptolemy)

– – Bar-Jesus (Acts 13:6)

– – Cephas (John 1:42)

– – “Abba” (Mark 14:36; Rom.8:15; Gal.4:6)

As discussed previously, Greek and Aramaic were prevalent in Jerusalem. Hebrew also played a role as a living language, as we are progressively showing in the course of these articles. Aramaic was commonly spoken by visitors to Jerusalem, and even by some inhabitants of Jerusalem. It has been suggested, for example, that Herod the Great and his family were native Aramaic speakers, since it is known that they were Arameans. In any case, the appearance of more than a dozen Aramaic-looking words, mostly names of people and places, with Aramaic morphologies is, contrary to many readers’ first instincts, not necessarily a particularly good indicator of the linguistic milieu of the New Testament.

As observed in our first study, the names of places tend to endure long after the language of a place has changed. Florida is full of Native American place names but virtually no one speaks the Native American languages anymore. Place names are not good indicators. Likewise the use of “bar,” meaning “son of,” rather than the Hebrew “ben” in so many New Testament names is not a reliable indicator. After all, we know from the New Testament that many of these men had Greek names as well. To give a contemporary example, even today children in New York may speak Hebrew or Yiddish in addition to English, but they still have a bar mitzvah. Likewise, many Israeli family names begin with “bar” even though these people do not speak Aramaic. They also refer to their father as “Abba.” Certain words penetrate and are universally used across language barriers. It is precisely because of these difficulties with the occurrence of single words in Aramaic that I chose, when possible, to focus on slightly longer instances of Aramaic (or suspected Aramaic) in my previous articles in order to be able to draw more solid conclusions.

It is evident that at least some portions of our New Testament, particularly parts of the Gospels, have been translated from Hebrew, and possibly Aramaic as well. (I make this distinction because there are tests to distinguish between Hebraisms and Aramaisms in a Greek text, and some passages of the New Testament indisputably come from Hebrew. Whether some other parts came from Aramaic remains an open question.) In addition, as some scholars have observed, when a document is translated from one language to another, often the foreign words, or words with very particular meaning, tend to be the ones that are left untranslated. For example, when a German book has a character that speaks certain words in French during the course of the narrative, if that book is translated into English, the French words are invariably left untranslated. Based on this logic it has been argued that the Aramaic terms littered throughout the New Testament would seem to point to Hebrew as the original language of many of these passages (since there are known Hebraisms in the text that cannot be from Aramaic.) This much is certain, but it is important to use caution when drawing conclusions like these.

Mishnaic Hebrew

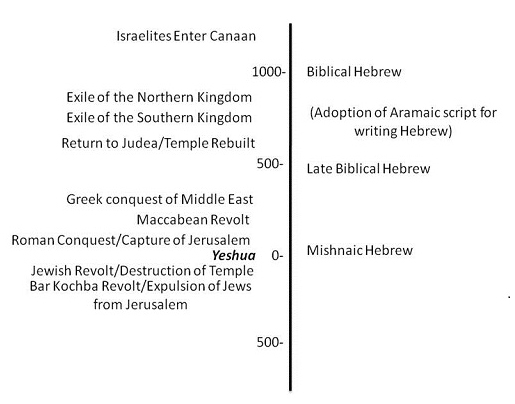

In the first article I sketched the history of Aramaic, so here in the third I will provide a similar overview of the history of the Hebrew language, with an eye toward giving some background for Mishnaic Hebrew, the Hebrew of the Late Second Temple Period.

At the end of the Babylonian exile the Persian conqueror Cyrus allowed the Jews to return to Judea and rebuild their temple, under the supervision of Ezra and Nehemiah. The Jews – at least the ones who actually decided to return, because many did not – came back to Judea with knowledge of Aramaic in addition to their Hebrew mother tongue. They also returned having adopted the use of the Aramaic script for writing Hebrew, in place of their old Paleo-Hebrew script. Using the Aramaic script they continued writing books in Hebrew, including many that became part of the Bible such as several of the minor prophets, Ezra, Nehemiah, Esther, some Psalms and probably books like Ecclesiastes. This Hebrew had a few distinctive features and is referred to by scholars as Late Biblical Hebrew.

In the centuries that followed the reconstruction of the Jewish temple in Jerusalem, other books were written in Hebrew that did not make it into the Biblical canon as well, such as The Wisdom of Ben Sira (c.160 B.C.E.), Tobit and the many extra-Biblical documents at Qumran. As Hebrew continued evolving Late Biblical Hebrew gradually became Mishnaic Hebrew (also known as Rabbinic Hebrew) which is what was spoken at the time of Yeshua.

Technically Mishnaic Hebrew is the dialect of Hebrew in which the Mishnah was composed. The Mishnah, an extensive collection of the sayings and teachings of rabbis, was compiled by Rabbi Judah the Prince around 200 C.E., contains teachings from the preceding centuries passed down from teacher to student verbatim, or nearly so, according to tradition. Mishnaic Hebrew compares to Biblical Hebrew much the way that modern English compares to King James English, and it tends to reflect a more commonplace, prosaic type of everyday speech vis-a-vis the more flowery, poetic nature of Biblical Hebrew.

So what do the rabbis behind the Mishnah have to say about the linguistic situation in Palestine?

Hebrew in Rabbinic Literature

(M.Eduyoth i.3, etc) חייב אדם לומר בלשון רבו “A man must speak in the language of his teacher.” This principle was carefully observed by the rabbis and as a result we have many instances in rabbinic literature where the language of the texts switches back and forth between Aramaic and Hebrew in the course of the discussion, as the point of view or speaker changes. Despite this strict adherence it is still not possible to say with 100% certainty that the language cited in a given passage of a rabbinic conversation took place in the language in which it is recorded, though this virtually always was the case. Nonetheless, many of these passages are indeed accurately preserving discussions in Hebrew. Presumably this principle of preserving teachings in the language of the teacher was more strictly observed for legal rulings than for anecdotes and stories; however, it is still interesting to read several of these rabbinic stories in light of this generally observed principle, because these stories present many characters speaking in Hebrew, and it’s difficult to imagine any other explanation apart from the possibility that many actually were speaking Hebrew.

Generalities aside, many sayings attributed to rabbis strongly suggest the use of Hebrew as a spoken vernacular. Rabbi Meir in the middle of the 2nd century C.E. said, “Everyone who is settled in the land of Israel, and speaks the sacred language…is assured that he is a son of the age to come.” (J. Sheqalim iii. 3; cf. J. Shabbath i.3) A few decades later Rabbi Judah the Prince (the compiler of the Mishnah) went further saying, “Why [use] the Syrian language [Aramaic] in the land of Israel? [Instead use] either the sacred language or the Greek language.” (B. Baba Qamma 82b-83a; B. Sota 49b). This statement seems to suggest that Rabbi Judah was encouraging people to keep using Hebrew. This implies that some were still speaking Hebrew in his day, as well as seeming to suggest that Aramaic was overtaking it, around 200 C.E.

There are still other stories about Rabbi Judah’s maidservant who spoke Hebrew, and whose conversation helped the sages to understand the meanings of some obscure Hebrew words. This clearly seems to suggest that Hebrew was a living vernacular for some people, even at the end of the 2nd century C.E. In the 3rd century Jonathan of Beit Gubrin said: “Four languages are most suited that the world should use them. These are: the foreign language (=Greek) for song; Roman (Latin) for battle; Syrian (Aramaic) for elegy; Hebrew for speech. Some say even Assyrian for script.” (Jer. Megillah i, 8)

Most compellingly, in rabbinic literature Hebrew had a special role and was used more frequently than Aramaic in certain genres such as prayer, storytelling and parables. It is fascinating to note that in all of the voluminous rabbinic literature there over 850 parables told, and they are all in Hebrew. There are no Aramaic parables! Even when the entire surrounding context and discussions are in Aramaic, the parable is related in Hebrew. This lends enormous credence to the suggestion that Yeshua’s parables were told in Hebrew as well.

When we looked at the words of Yeshua on the cross we encountered an example of the use of Mishnaic Hebrew, the descendant of Biblical Hebrew that we have been discussing. As mentioned in the previous study, the Mishnaic Hebrew character of the sentence Yeshua spoke on the cross, “My G-d my G-d why have you forsaken me,” can be discerned in the use of the word “sabachthani” (= שבקתני = “forsaken me”). This example illustrated how Mishnaic Hebrew can be very helpful for illuminating a number of difficulties in the New Testament. Now we will take a look at a second, classic example of how Mishnaic Hebrew can give us insight into the New Testament – in the visit of the women to the tomb, as recorded in Matthew 28:1:

Now after the Sabbath, as the first day of the week began to dawn (Οψε δε σαββατων τη επιφωσκουση εις μιαν σαββατων), Mary Magdalene and the other Mary came to see the tomb.

Matthew 28:1 has been a puzzle, particularly for Greek scholars, for a long time. A more literal translation from the Greek would be “Late [of] Sabbath in the lightening [dawning] of the first of the Sabbath…,” which seems like an extremely strange statement. As it stands this sentence actually makes no sense. As it turns out this bizarre phrasing is actually a very literal translation of a phrase in Mishnaic Hebrew: במוצאי שבת, אור לאחד/לראשון בשבת. The confusion seems to have arisen because of the idiomatic expression “אור ל-“ which means “light of” and seems to have been misunderstood by later copyists or Greek writers who assumed that this “light” must refer to sunrise. Actually this idiomatic phrase refers to the rising of the moon, indicating the end of the Sabbath and the start of the new week. Thus the visit of the women to the tomb in Matthew 28:1 took place on Saturday evening, immediately following the Sabbath. This is not reflected in our Bible translations and is almost universally unrecognized among Bible scholars and laypeople alike.

In the next installment we will briefly survey what Josephus, Qumran and archeology can tell us about the linguistic world of the messiah in the first century C.E., with an eye toward further insights this can give us into the message of the New Testament.

Author: E.A. Knapp